The Silent Battleground

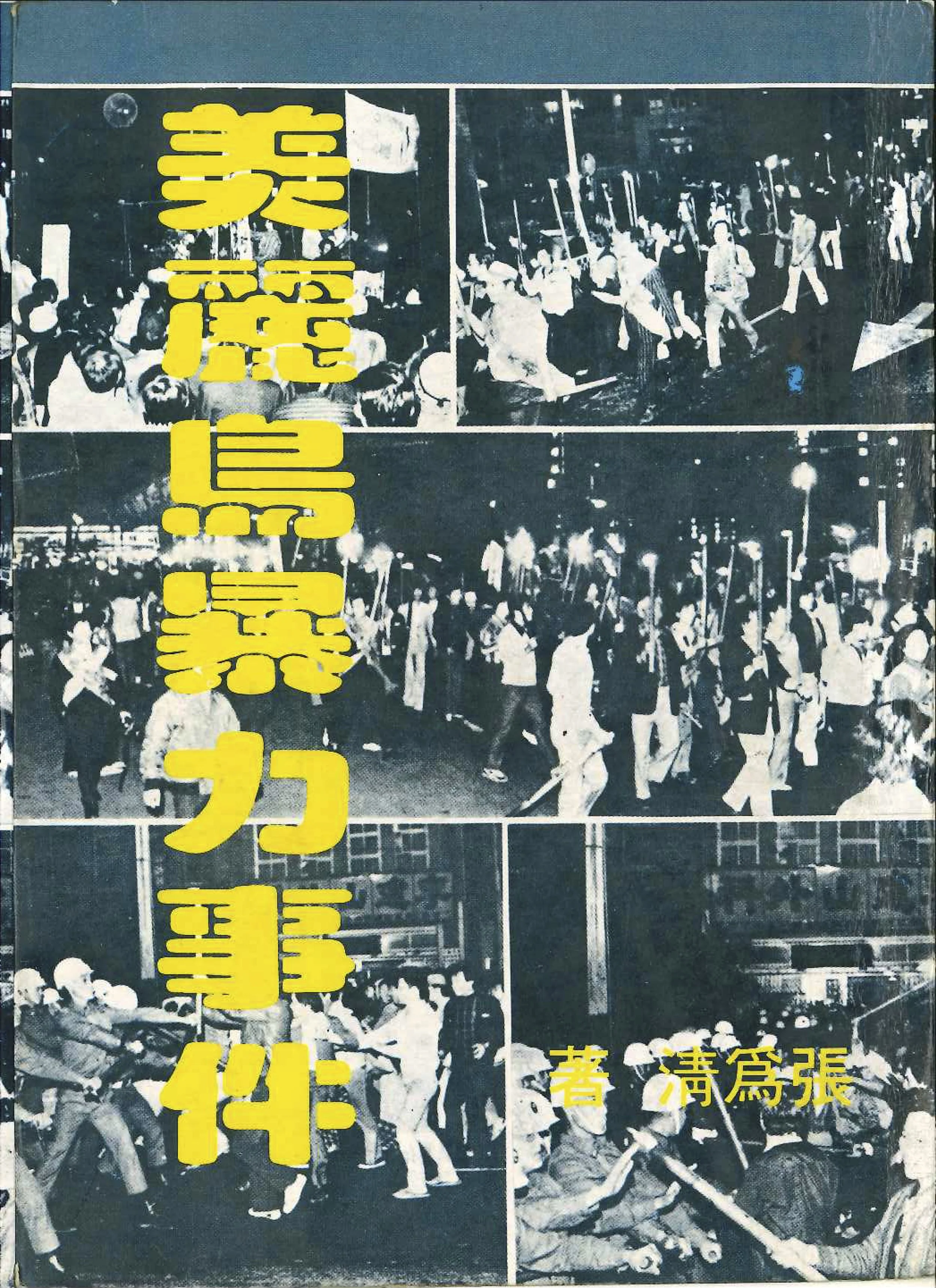

A couple of years ago, while I was studying at Uni of Westminster, I stumbled upon this photography magazine published during Taiwan's martial law period by the authoritarian government—"The Formosa Incident." This event was a crucial turning point for Taiwan's politics to transition from a party-state authoritarian regime to full democracy, as it indirectly led to the lifting of martial law by the Kuomintang (KMT) government in 1987, which had lasted for 38 years.

In the late 1970s, Taiwan was at a crossroads of transformation. The "Formosa Incident" erupted from a peaceful rally intended to celebrate International Human Rights Day. However, the rally quickly escalated into a standoff with the government, resulting in the arrest and torture of several pro-democracy leaders.

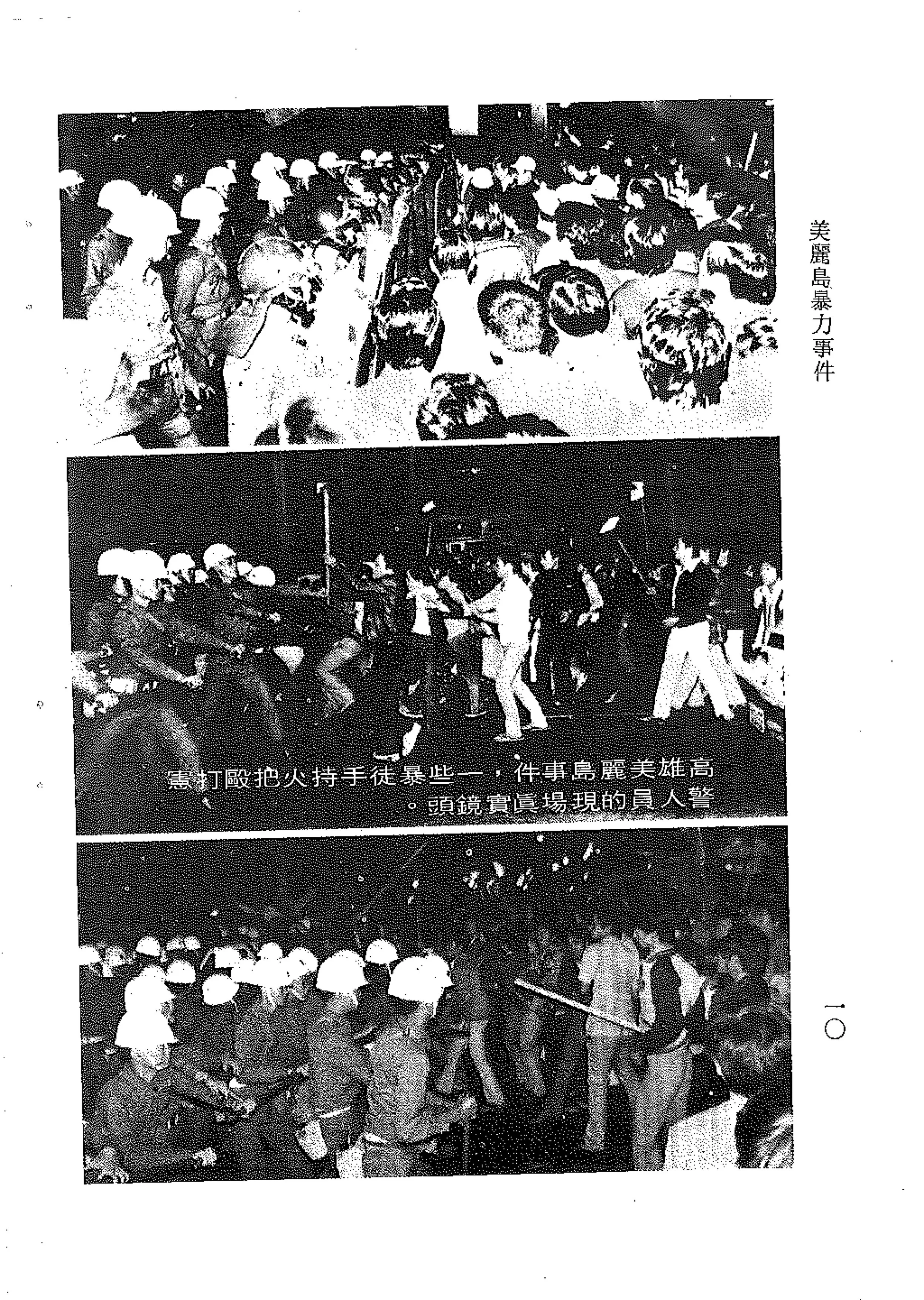

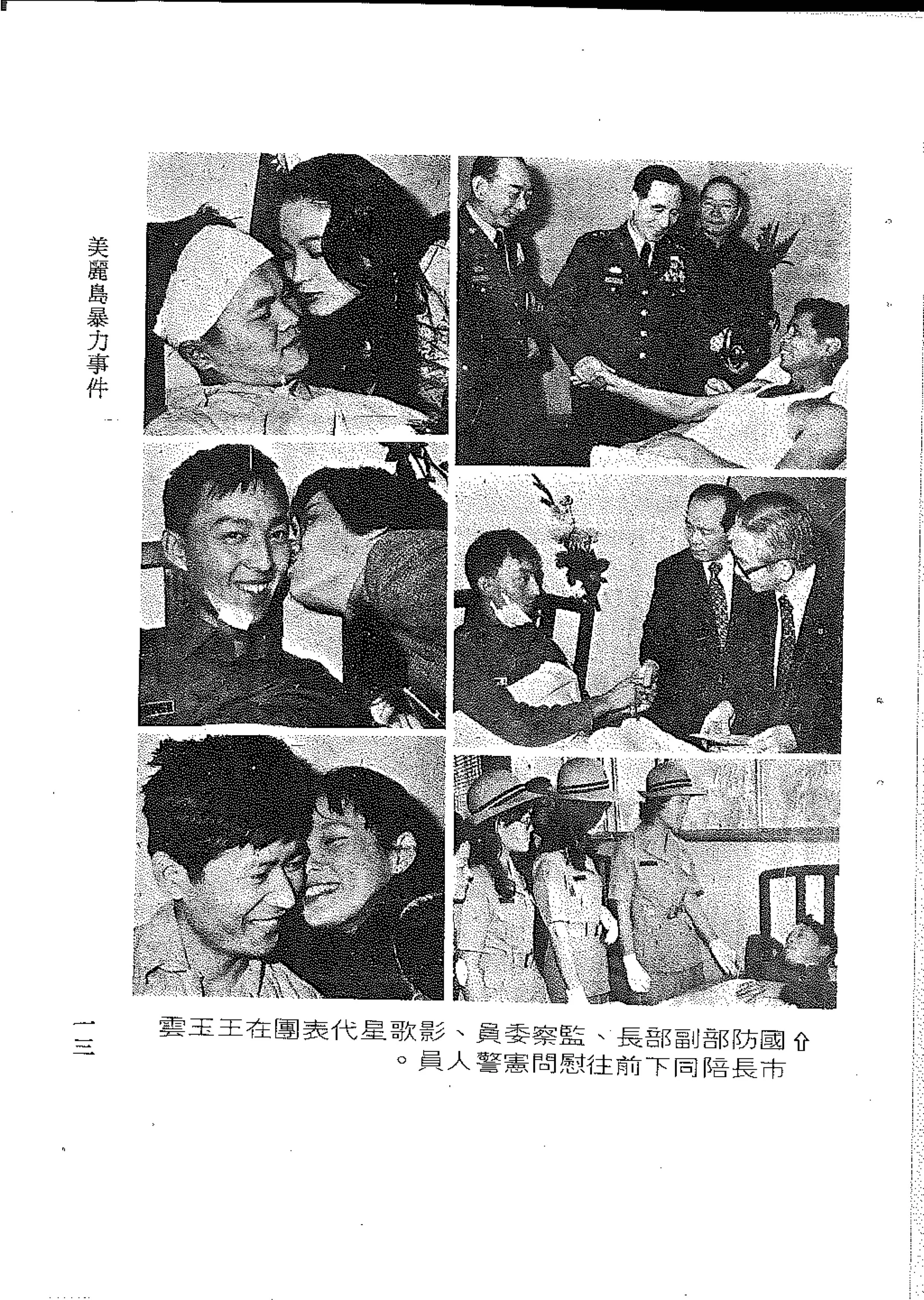

Afterwards, in an attempt to control public opinion, the government used various media, including photography, to depict the activists as a group of violent instigators attempting to collaborate with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to overthrow the Republic of China (R.O.C, which is known as Taiwan in nowadays) government. This aimed to confuse the public and conceal the truth, and "The Formosa Incident" magazine was a prime example. The publication used a combination of images and text to justify the government's military crackdown and sway public support. (Ironically, although the magazine intended to demean the activists, it included the full transcripts of their speeches, unintentionally becoming a platform for them to be heard. )

Such propaganda tactics are not uncommon under authoritarian regimes. In the modern history of East Asia, whether it's the reporting of the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident or the records of the Hong Kong riots in 1967, we can see how the same images are endowed with entirely opposite narratives to control public opinion. In the case of the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, the same photo of an injured soldier being helped by students was described by the Associated Press as "A captured tank driver is helped to safety by students as the crowd beats him," whereas under the Chinese government's description, it became "a tank driver being dragged out and beaten by students."

In Western media, it is described as “A captured tank driver is helped to safety by students as the crowd beats him.”.

Source: June 4, 1989. REUTERS

In the similar image, it is described as “The cadres of the martial law forces who were injured by the mob.”.

Source: “Defenders of People’s Republic”, published by the Propaganda Department of the Political Department of Jinan Military Region

During the leftist riots in Hong Kong in 1967, the leftists and the government coincidentally used video publications as an extension of their will. The leftists published the album "Atrocities Whose Crime", accusing the police of using excessive force. Soon after, the Hong Kong government launched the People's Advocate, which was similar in design and style. In addition to this, it included photographs that were very similar to those in the leftist publication, but the narratives were completely reversed.

The once-honored values of photography as a "witness to truth" and "objective record" have long been challenged. As an important medium for propaganda, the political nature of images has been effectively utilized. The spokesperson for the truth no longer belongs to those holding the camera. Instead, how images are "represented" and "interpreted" has become the real battlefield.